Real World Tales

Aviation Prose & Anecdotes

Real World Tales

Aviation Prose & Anecdotes

Last Updated June 24, 2008

Welcome to Flight Flap. Here, you'll find real-world flying stories submitted by WestWind pilots for your reading pleasure.

![]() Have a story to

contribute? Click here.

Have a story to

contribute? Click here.

"My Trip to

Southwest Asia"

By Mark Chapel, Hub Manager, YVR

(November 20, 2005)

In September of this year, I was invited by the Canadian Forces Personnel Support Agency to be part of the crew (in the real world, I work as a freelance sound engineer) for their Show Tour of Southwest Asia and the Persian Gulf during October & November. The Show Tours are very much like the USO shows put on by the U.S. military – except that all of the entertainers are Canadians.

One of the four locations we played does not "officially" have a foreign military presence – despite the fact that Canada, Australia and New Zealand all have troops at a base there called Camp Mirage. Although I’m unable to publicly mention the "host nation" or the nearest city by name, I am able to give hints that should help you fly to that location – that is if you decide to re-trace my steps in the form of a WestWind Charter flight.

After five days of rehearsal and one show at CFB (Canadian Forces Base) Kingston, we boarded a bus for the 50-mile trip to CFB Trenton (CYTR) where we boarded a C150 Polaris (the military version of the Airbus 310).

Passenger accommodations were limited to seven rows of 8 seats at the rear of the aircraft. The rest of the space was taken up supplies destined for Canada’s military and humanitarian efforts in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Things weren’t too spartan in the passenger compartment, though – most of the amenities (including the in-flight magazine and movies) were from Air Canada. Unfortunately because of the cargo wall ahead of us, we were unable to visit the flight deck.

We departed Trenton at 7:00pm local time (2400 Zulu) just as it started to rain and arrived eight hours (and six time zones) later in Zagreb, Croatia (LDZA) to re-fuel and continue on to the Persian Gulf. Strangely enough, the weather was almost identical to the weather back in Trenton! I was surprised at the number of business jets (mostly from the UK and Germany) at the airport. I was strongly advised NOT to take any pictures of the bizjets, but that it was OK to take a picture of our own aircraft with the crew stairs in place.

Although we were scheduled to be in Zagreb for 90 minutes, the North Atlantic jet stream was particularly brisk that evening and we arrived an hour before our designated refuelling stop, so our stopover ended up being slightly less than three hours. It’s amazing how many $1 espressos you can drink in that amount of time. Even more amazing – if you’d prefer instant coffee (why?) it costs twice as much!

Back onto the Polaris and four hours (two more time zones) later we were over the Persian Gulf – but well away from the "activities" in Iraq. After another hour, we reached our initial destination (OMDM) at 8:30pm local time (1630Zulu) and the temperature was 32 degrees – Celsius! After a briefing regarding local customs during the month of Ramadan and the dangers of camel spiders we went off to our quarters (air conditioned "portable" buildings) and slept.

After a day’s worth of recuperating from jet lag, a set-up day, a day of rehearsals and two nights (because daytime temperatures were in excess of 42 Celsius – or 107F!) of shows, we reported to the "stores" depot. There, we picked up our flack jackets, helmets and anti-malaria medication in preparation for our trip to Kandahar, Afghanistan the next day in a C130 Hercules.

"this is the only photo I was allowed to take at Camp Mirage"

We departed OMDM in the early morning because the forecast called for the temperature to be 45C (113F) before noon. That would put our density altitude at nearly 4500 feet when our field altitude was only 168 feet MSL! Our route took us over the Gulf of Oman – well south of the coast of Iran – and over the northernmost part of the Arabian Sea. As we made landfall over southern Pakistan, I was invited onto the flight deck. The Herc flies with a crew of four in the "front office"; Captain; 1st Officer; Flight engineer; and Navigator. Even with all of those people up front, there was ample room for three "visitors". Note: See the pictures in the WWAL "Photo Album"

| "looks just like the WWAL C130 panel ! " | "I didn't really have to sit with the cargo, but, as you can see, some folks thought it made a great sofa" |

As we descended into Kandahar, we were instructed to don our flack jackets and helmets because - for the last 10nm of the trip – we’d be doing some tactical flying. Tactical flying??? Think of the most intense roller-coaster ride you’ve ever been on and double that sensation. Then think of doing it with your eyes closed – because in the back of the Herc, there are no windows to see out of.

After we disembarked at Kandahar AirField –( OAKN) a.k.a. KAF -, we were given a quick briefing on the dangers of IED’s (Improvised Explosive Devices), land mines and walking alone at night. We were also given an explanation as to why all 19,000 military personnel (from many countries – including; the US, Canada, Great Britain, Romania and France – yes - France!) on the base were required to carry a weapon at all times. Then we were shown to our accommodations....

After another day of recuperation after our 3-hour flight (and a chance to acclimatise to the ever-present dust (commonly described as finer and slightly drier than baby powder) a few more days of set-up and rehearsals, we performed two more shows to rave reviews.

The next day we were to perform in the City of Kandahar for the Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT). These guys work in a constant state of readiness because the Taliban is still active in the area. Our ground transportation into the city was up to the task – an 8-wheel-drive Bison armoured personnel carrier, capable of sustaining multiple hits from .50-calibre ordnance…

Upon our return to KAF we were advised that the Taliban had launched a rocket in our direction which landed less than 500-yards away. There’s no doubt that they were trying to send us a message because there hadn’t been a rocket attack within 5 miles of our location in the past two years!!! Needless to say, we were more than happy to be on our way back to Camp Mirage the next afternoon.

We said our good-byes to our hosts at KAF and headed to the terminal. Unfortunately it was not the terminal that you can see in the picture of the 727 which was built in the early ‘70’s – 25 years of strife in and around the airfield have rendered it unusable for the time being.

We got back into another Herc, but this time I was invited into the cockpit for the take-off! Again, we were instructed to do some tactical flying for the first 10nm before proceeding on course. After take-off, we levelled off at 200feet AGL and held an airspeed of 150IAS. Every 30 seconds for approximately four minutes we initiated a rapid (30-degree bank) 45-degree course change. Upon completion of the tactical flying, we made a 2.5G full-power climb to 2,500feet AGL and then continued our climb to 17,000 at 1,000FPM. A little later in the flight, I was invited to take the left seat – with the autopilot off! It’s a good thing it was dark – you can’t see me sweating in this pic…

After a few more days of relaxation, shopping and hanging out on the beach in the city just north of Camp Mirage, it was time to head home. We boarded another Polaris en route to Zagreb and used up almost all 10,000 feet of runway on takeoff because we departed at 2:00pm local time – during the hottest part of the day!

Shortly after takeoff, our captain pointed out this island off our left wing – it should give you a hint as to which city Camp Mirage is near.

Our fuel stop in Zagreb was much shorter this time. We were on our way again less than an hour after touchdown! As we levelled off, our captain informed us that the winds over the North Atlantic were working against us and we’d have to top up the tanks at Prestwick (EGPK) Scotland. I had just obtained some UK funds from the ATM to buy some souvenirs when I was told we were departing in five minutes. It seemed like it would take longer to re-fuel my car!

We arrived back at Trenton a "scant" 16 hours after our original departure. Clearing Customs went much more smoothly than I anticipated (those Marlboros for $10 a carton are still haunting me from Kandahar) and I was quite surprised to see my wife waiting for me in the terminal. After a (relatively) short two-hour drive, I was very happy to be back home in my own bed.

I have intentionally left out many things in this story. This is partially because the Canadian Armed Forces requested that I be very circumspect about exact details. Also, I don’t feel it’s appropriate to impose my views on the geopolitical situation or to discuss my personal feelings about many of the events that took place while I was overseas – especially not on WestWind’s site. If you’d like further details about any aspect of this story, feel free to send me an e-mail.

.jpg) |

"Welcome

aboard COBRA 66 Mr. Ambassador" Most pilots when sitting in the pilots lounge will compare themselves with others based on the equipment they fly. Bigger, faster and newer equipment are generally accepted signs of success. That is until you have re-found the simple pleasure of flying low and slow. So why is it that I find so much fulfillment in flying a 30 year old King Air? Well it is not the airplane, although I personally believe the King Air is the best machine built for executive aviation. Inexpensive, nimble and relatively fast for $3.5 million. For me the pleasure comes in who it is that I am transporting.

|

Welcome aboard COBRA 66 Mr. Ambassador.

I am one of a handful of pilots chosen to fly executive air transportation. What is it like to fly the Ambassador? Well it is like every other mission. Just the pucker factor is way up.

The flight begins like any other flight, with mission planning. We start weeks out for executive transportation, when we get the heads up. Unlike our civilian counterparts we have to file for diplomatic clearances for the aircraft to fly. This is the host country giving us permission to fly and land on their sovereignty. Much like Air Force One, Cobra 66 is also the United States of America. Where ever it goes it is America. When foreign air enters the front of the aircraft, it becomes American air until it goes out the back end, no longer needed for pressurization. The soil on your feet, gets ground into the carpet and becomes American soil until it is vacuumed up and disposed in the trash container and given back to our host nation. The other parts of flying the aircraft are much the same; weather briefings, NOTAMS, itinerary planning, and filling our ICAO flight plan, with the /RMK DISTINGUSIHED VISITOR DV-3.

The night prior to the flight I spend reviewing the flight. If I have time I may even fly it in FS9 to work out any issues. I review the charts looking hard at the approaches. SIDs and STARS can be gotcha so I review them. I print out my package with including any JEPPVIEW charts on the airport and our Form 70s. Then it is off to bed early.

I am picked up in the morning by one of our drivers. In route to the airport I brief the mission to my co-pilot, covering route of flight, weather, NOTAMS, risk assessment, and any other pertinent information. We are expedited through the airport and given our final weather update and NOATMS. At the aircraft we perform our interior and exterior checks as well as check the book for previous squawks. As we fly the same airplane all of the time we generally know all of the “aches and pains.” Thirty minutes prior to pickup we crank, run through out before taxi, engine run-up checks and pickup our clearance and taxi instruction to pick up our passengers. Almost all of out pickups are done engines running, we feather the number 1 propeller, lower the flaps and the crew chief opens the door and loads the passengers. We will make last minute coordination for departure.

COBRA 66 is not designed as a flying office, if the Ambassador needs to do any work enroute it will have to be on his laptop. We have no special air to ground communication, yet (SATCOM is in our future.) Thus despite having a dedicated aircraft, it is not much different then flying on an airliner. We do have a lavatory, if needed and we can order catering and carry cold cut sandwiches or other small items for long trips. There is no in-flight kitchen or a steward to prepare items, and defiantly no wet bar.

Approach and landing are the same as any other flight. We know that despite landing compromising less than 1% of the flight, we will be judged on how firm the aircraft touches the ground. We will taxi to where a motorcade awaits of visitor, and unload. Then it is reposition and shutdown. We will then enter the pilot’s lounge where we meet with other pilots who may be hanging around. It is always the same, after seeing the motorcade depart they become very interested in our 30 year old King Air, with UNITED STATES OF AMERICA painted above the windows. “You must have some really advanced stuff it there” is often the response. I usually chuckle and say yea. I don’t want to burst their bubble by telling them that a Cessna 172s coming off the line today has much more advanced avionics than us.

-Ken

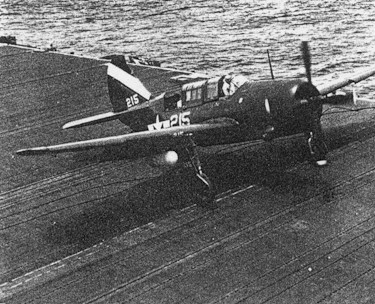

"Belching Beast - The SB2C

Helldiver"

Off Saipan and the Aircraft Carrier Lexington - Heading toward

Japan...

By Gene Popma,

WWAL CEO

(September 26, 2000)

|

November 6, 1945 "About 50 miles into the flight I noticed small drops of oil hitting the windscreen. I requested departure from the formation to return to the USS Lexington..." LTJG Gene "Hotrock" Popma Earlier in the year, Gene visited the National Museum of Naval Aircraft

in Pennsicola to see his "old friend" #83479, the actual SB2C Helldiver

aircraft, that he flew on that day, some 55 years ago. The museum has published Gene's

heroic adventure in an article called: On Deck at the Museum - The Belching Beast. |

"The C-17 Globemaster

III"

By James Italiano

(April, 23, 1999)

I have just been selected for retraining into a new career field. I am going to be a Flight Engineer on USAF C-130 aircraft. I am currently an avionics specialist on F-15's. I am really excited as now I no longer dream of flying but will get to do it on a day to day basis!

Recently I had a chance to take a ride on one of the Air Force's newest cargo / transport aircraft, the C-17 Globemaster III. Throughout my 12 years in the Air Force I have flown in just about every transport aircraft we have including C-5's, C-141's, C-130's, KC-10's and KC-135's. Some are better than others with the KC-10 being the most comfortable with regular airline seats and the C-130 being the most "austere". Web seats and a constant vibration from those 4 Allison T-34 engines making for an interesting ride. The first thing you notice about the C-17 is that it appears to be all engine. 4 Pratt & Whittney F117 PW100 engines produce 40,400 lbs of thrust each. By the way, these are the same engines found on commercial 757 aircraft.

The plane itself resembles a C-5 combined with a C-130. Kind of an awkward looking bird. You enter the main cargo area through a side hatch on the left side. It has a boarding ladder built in, much like a regular passenger turbo prop aircraft. Seating is along the sides of the aircraft with web seats in earlier models and plastic fold down seats in the newer versions. Not much comfort. Luckily they do provide any passengers pillows and blankets. These immediatly went under my butt. Looking around the cargo bay you notice how spacious it really is. The ceiling is unusually high and all the wiring and "plumbing" is in plain view. The loadmaster sits in the cargo section at a station on the forward right side of the airplane.

The C-17 is unique in that it only has a crew of 3. Pilot, co-pilot and loadmaster is all that is required. Loading and unloading of cargo is done automatically through the back ramp, with any weight and balance calculations done on the loadmasters computer. We strapped into our "seats" and the loadmaster prepared for takeoff. We were flying from Elmendorf AFB, Alaska to Yokota AB in Japan. Flight time would be about 9 hours at 35,000 ft with a IAS of about 350kts. The pilot lined up on the runway and ran up to max power. As we shot down the runway you notice one thing right away, the awesome power of those engines! I have never been thrown back (sideways) from an airplane like that ever. We actually got to do this twice as the first attempt at a take-off resulted in a high speed abort. An "APU" light on take off roll had come on. After the pilot reset the light we turned around tried it again. This time we got airborne no problem. Climb-out to cruise altitude was pretty normal and I settled in for some reading and sleep. By the way, I was reading Tom Clancy's Fighter Wing. It is must reading for anyone interested in how the Air Force does business, and it is about my first base, the 366th Composite Wing at Mt. Home AFB, Idaho!

After about an hour or so the pilot came down to see how his passengers were doing. I was the only one awake. One other thing about the cargo area on this plane, it was cold, real cold! So when he asked me if I'd like to come up to the flight deck (politically correct term for "cockpit") I jumped at the chance. To get there you climb up a ladder and pass through the sleeping area which can accomidate an additional crew for really long hauls. On this flight we had an exchange pilot from the British Royal Air Force. The cockpit is very spacious. There are 4 seats: pilot, co-pilot and one seat behind each of these. The seats are very comfortable and adjustable in every way you can imagine. After getting plugged into the comm I sat down and took a good look around. The view out of this airplane is incredible. There seems to be windows all the way around. Big windows. Then you notice the instrument panel. Four MFD's fill the console. A wide variety of information can be brought up on any of them. One had engine data displayed, one had a EADI, one looked like NavDash and the co-pilots also displayed an EADI. Between the pilot and co-pilot seats are the throttle quadrant and the most amazing FMS you have ever seen. It consists of 4 computers (2 for the pilot and 2 for the co-pilot) that can navigate the entire flight plan from take-off to landing. TACAN, GPS, VOR and who knows what else can be programmed in quite easily. The autopilot panel resembled that of any large commercial airliner. (Take note, Eric Ernst does produce the MOST accurate panels out there, many thanks to him!) This plane is also equipped with a Heads Up Display, which being a fighter mechanic, I found most interesting. It displays most of the normal flight data you would find on any HUD system in use today. The C-17 is designed to do alot of different airlift operations and that includes low level drops in adverse weather. Having a HUD eases much of the workload put on the pilot in these instances as well as having the pertinent information for landing right where he wants it. The rest of the cockpit contains your standard switches and buttons.

Many of the same systems found on commercial airliners are in use on the C-17, auto throttle, ect... Circuit breakers and engine switches are located on the overhead panel along with fuel and air conditioning systems. The caution panel is unique in that it is a LED readout as opposed to a standard "lights panel" that is located on the center panel right above the autopilot panel. Landing at Yokota AB was quite interesting. The first thing I saw coming into the area was Mt. Fuji out the right window. Pretty impressive piece of real estate to say the least. The pilots opted for a high angle descent due to the many noise abatement laws Japan has implemented. There was so much going on that I could barely keep up. It was a rather steep approach being roughly 2500 ft/min descent. The ground filed the front window. I did notice that the pilot used his autopilot for the approach until we were about 500 ft AGL, where he took over manually and made a very smooth landing. Landing speed was right around 120 knots or so, and once the thrust reversers kicked in it didn't take long to stop. To my dismay I was not going to finish my journey on the C-17. The rest of the trip back to Kadena AB, Okinawa Japan was to be made in a C-130 aircraft. Luckily it is a short flight, 2 hours.

My thanks to that C-17 crew for allowing me to check out their airplane! As soon as I get my incentive flight in an F-15C, I'll let you all know how that goes too!

"Murphy and Me!"

"Murphy and Me!"

By Bryan Andrews

(April, 13, 1999)

All pilots know Murphy. He is better known as the CEO of "Murphy's Law, Inc." When you are learning to fly, as I was at the time, you don't worry about Murphy very much. After all, you most likely have a competent person with you to fix whatever goes wrong.

Murphy and I had a little meeting one September morning. That's right. "We", had a meeting. Him and Me. One on One. Mano y mano. With 12.2 total hours, I set off to do what I had lay awake in bed at night losing sleep over Soloing. My instructor, Don White, is a 737 Captain with over 8000 hours. On top of that, he is a friend of mine. I was pretty sure he wouldn't have put me in that situation if I wasn't ready.

We were flying dual for the first half hour that day, when all of the sudden, he has an urge for a cup of coffee. (I think he said that he had to use the restroom, also. What a corny CFI excuse..<grin>) It was a beautiful day. Blue skies, cool morning air, and a 9 knot headwind out of the west. So, I drop Don off at the flight line, and taxi down to runway 26, Front Range Airport (FTG), Watkins, Colorado. I call for a field advisory (just for the pure hell of it), insert a fresh Copenhagen chew in my lip, a drink from the water bottle, and I'm ready.

With runways long enough for an aircraft as large as a 757 to operate on, I don't bother to position. Just taxi past the numbers, turn the transponder to ALT, and hit the juice. (That way I had less time to think about what I was getting myself into) A short takeoff roll, a gentle pull on the elevator, and I'm flying with the hawks. I remember thinking how well the Cessna 172 climbed out with just myself on board. <g> I'm feeling pretty good, no nervousness at all. Planning on shooting four or five touch and goes, I enter the left crosswind, then the downwind.

Now, remember how I said Mr. Murphy and I were gonna "throw down"? (round

one, ding-ding)

The time it takes to fly one pattern at FTG is about three or four minutes. As I

entered the left base for runway 26, I heard Don call me on the Unicom. "Hey

bro, why don't you make this a full stop, the winds have picked up quite a bit"

Okay, no problem. I'm thinking that they picked up over 15 knots, and still blowing

down the runway. Wrong, 18 knots and a bitchin crosswind. FTG has a

north-south runway that I could have used, but of course it is closed for repaving. (round

two, ding-ding) I didn't know it was 18 knots until after the fact, but believe me,

I saw the wind sock! I'm starting to feel a little bit of anxiety at this point as I

turn to final, but I'm not a wreck quite yet. (At the time, most of my crosswind

experience had come on my introductory night lesson, so I felt pretty good) Here I

come (Hail Mary, Full of Grace), crabbing like mad. "Aileron into the wind,

apply opposite rudder" Sweet, I'm looking good! The wind has a tendency

to GUST on the Colorado Plains. (round three, ding-ding) A big gust hit my little 172

right as I was about to settle in. We balloon over the runway. Back in

control, and falling back to Terra Firma, I add some power to cushion the landing. (Don is

a kickass flight instructor, I might add) Another gust, and I'm off toward the edge

of the runway as the aircraft settles down. To hell with holding the nose gear off,

I need it to steer! I give the nose some help to settle on the runway and I am

steering back to the centerline, when I am hit with yet another big gust of wind.

Out of the corner of my eye I can see (and feel) the left wing starting to rise. I

jabbed the aileron to the left to keep the aeroplane from ground looping. Back in

control, again, I get back on the toe brakes and start to slow down. I finally taxi

off, past the hold short line, and stop. And let me tell you. I was as scared as I

have EVER been in my entire life. My body was trembling so bad that I could barely

turn the transponder to standby much less retract the flaps and turn off the carb

heat. Taxiing to the flight line, I see Don, and the owner of the flight school

waiting for me. Don has a grin on his face, and the flight school owner looks a

little pale. To hear Don tell it, the owner was doing some body English the entire

time I was landing, kind of how a football coach reacts to a field goal kick. I got

a few "atta boys" from the people at the school, after that ride. The

owner of the flight school didn't say much at the time. Every once in a while, when

I call him to schedule an aeroplane, he recounts little pieces of that story to me.

And he always ends with, "I'll never forget your first solo. You handled that

landing really well." I'll never forget it either. Oh, and Mr.

Murphy....we traded a few good hooks. I learned some valuable lessons from

you. I'll probably see you a few more times in my flying career. I guess

that's how it goes.

"Alone at Last!"

"Alone at Last!"

By Matt Kaprocki (14 years old)

(January 13, 1999)

Well, maybe today’s the day. After a couple of months of taking my glider lessons to get my student pilot certificate, I felt ready to complete the task of soloing. We had just landed from the first flight of the day after just circling around the field. I was sitting in the front seat of the Scheiwzer 2-33A sailplane, the only plane I knew. Waiting for my instructor to take his usual seat behind me for another normal flight, I hear him tell me that the sailplane would takeoff earlier and I would need a little more down elevator on the aero-tow because it would be a little lighter without him on the plane. “WHAT?!” I couldn’t believe my ears. It was finally time for me to solo. Sitting at the end of runway 09 thinking “what did I get myself into?” Well, it was time.

I gave the standard thumbs up signal for my wing runner to raise the wing. Then the rudder waggle telling the towplane pilot I was ready for takeoff. As we started down the runway, the strangest thing happened to me, I felt all my fear just disappear as if it were another normal flight. Though the aero-tow was a little more bumpier than usual, it was nothing I couldn’t handle. As we reached 1800’ AGL, I pulled the release handle and I was off. I was all alone.

Now I was down to 1000’ AGL. Time to land. I ran down the checklist posted in my sailplane as usual. Downwind, base, now turning to final. Touchdown. I had done it. I had soloed an aeroplane. The sky’s the limit!!

Archer

02, You're On Fire!

Archer

02, You're On Fire!

By WestWind's Clayton T. Dopke (Drac) Major,

USAF retired

September 12, 1998

I wanted to share this with you. I wrote it several years ago, just so I would always keep the facts straight, and as closure to a part of my life which became very troublesome. Hope you enjoy it.

I vividly remember the day, 26 December 1972, for three very significant reasons: First, it was the day after Christmas - not a good time to be at war - and Christmas for some reason, would never be the same again. Second, the wing was finally getting the opportunity to go to Hanoi and get some seriously needed pay back. This time, because of the peace talks break down, we were in the attitude adjustment business. And lastly, it was my 202nd combat mission as an aircraft commander in a B-52D . . . and my final flight in a Buff. The Voluptuous Vampire, as my seasoned crew lovingly referred to the ‘D' would receive the fateful stake in the heart . . . dying an untimely death in battle that day.

Our mission was to deliver our package . . .eighty-four - 500 pound bombs internal and twenty-four - 750 pound bombs affixed to the hard points on the wings . . . to the Hanoi RADCOM station 11 south. Every airman in Archer cell knew we were not the first wave of B-52's to try to eliminate this target. This was to be a surgical strike on military targets only. Was that possible with 60,000 pounds of dumb-bombs and from an altitude of 35,000 feet? During the morning briefing, we were constantly reminded that should we not be sure of the target, we were not to release, as this was not an Arc Light carpet bombing. During the long flight from Guam I wondered how many pilots and crews would willingly carry out that order.

Takeoff from Andersen AFB, Guam was orderly and uneventful; we were the number two aircraft in Archer (the lead) cell. Six cells of B-52's, consisting of three aircraft each, had a date with North Vietnam and its heavily fortified and defended airspace. There were no illusions . . . Hanoi was Sam City and the SA-2 sites were manned by expertly trained men on a mission . . . to kill the American bombers. Hanoi's radar integration of SAMs, MIGs and AAA made it the most heavily defended area in North Vietnam. . . and perhaps at that time, the world. Although we didn't dwell upon it, the thought that some of us would not return lingered in the atmosphere. No one even dared mention it, but each of us prayed to his own God, asking that if someone had to die this day, let it be someone else . . . not a very gallant thought.

Somewhere north of the Philippines, we snuggled up to a KC-135 tanker and took on our maximum load of JP4 - jet fuel. Air to air refueling was emotionally taxing at its very best, however on this day, it would seem mundane and sedate. At that point, not even having hooked up with the remaining cells of the strike force, my alarm status was on full tilt. I guess it showed as my number 2, Capt. John Learner, (a man who was proven to have ice water running through his veins) said to me: "Relax, Drac, sir," - always using Sir, after my nickname - "we made 201, we can make 202." Two hundred missions hadn't included going to Hanoi. Route Pack 6 - the area designated for Hanoi and Haiphong harbor - were the ultimate badlands.

Command had us on the direct route to Sam City. Guam-based Buffs were vectored two directions this day. Ours, the direct, ran up the coastline almost to Haiphong, where we then turned inland. The second, being what we laughingly called the scenic route, ran you inland into Cambodia, crossing Laos, Thailand, then Laos again until you were on a direct heading for Hanoi. In actuality, it was a coin toss which path put you further into harm's way.

Off the coast, almost parallel with the border between the North and South, we picked up our rendezvous with another ten cells of aircraft. Each of us had a position in the long chain of Stratofortress' according to the ordinance we were loaded with. What a photograph that would have made . . . aircraft stacked five-to-six hundred feet apart, with each cell being two miles to the rear of the previous one. Our cell was fourth in line . . . we wondered if Charlie would have his Fan Song radars dialed in by then. Charlie always knew you were coming to dinner.

Passing Red Crown, a radio relay ship in the Gulf of Tonkin, we bumped altitude to the full 35,000 AGL and moved inland skirting Haiphong and onto our target in Hanoi. By this time we could hear the beginning of serious radio chatter from the F-4 Phantoms who had laid down the chaff corridors fifteen minutes earlier to confuse Charlie's radar. F 105-'s were doing their iron hand- hunter-killer routines against unlucky SAM sites who painted them and the area was beginning to get very busy.

I remember getting on the intercom to Lt. Chambers, my EWO. "Stay sharp back there, we don't' need any surprises." Jerry Chambers was an excellent Electronic Weapons Officer and had a special knack reading the tube and second guessing the enemy to protect us from surprise SAMs and MIGs.

"Roger that," was his only reply. I could tell he was keeping busy and didn't need my continued mother-hen prodding.

At about ten NM from the target I could see that the cell directly ahead of us was being swamped with AAA fire . . . the harmless looking puffs of black soot enveloped the three Buffs, however I did not see a single hit. Good for them, bad for us. It was at this time I began to monitor the SAM calls from the first two cells of aircraft ahead of us. In retrospect, I don't believe I could keep have kept track of them all as there were so many . . . the SAMs didn't need to get the altitude and range right . . . they constantly reconfigured on their target. Yet at this point, neither the cell ahead of us nor ourselves had received a single SAM liftoff signal or sighting which was directed our way.

"60 seconds to release," the call came over the headset. "Pilot, center the FCI" (Flight Command Indicator to establish the proper bomb run heading).

"Ten degrees left and centering," I replied. Once centered, we were committed and I would not deviate on our course until bomb release. "Bay doors," I called out.

"Not yet," I heard the RN's voice. "Wait." He was going to tarry till the last instant to open the bomb bay doors so as not to increase our already huge radar signature.

"Thirty seconds," Capt. Paul Jackson the RN called out.

I was checking to make sure my BDI was centered, (bomb direction indicator) when the EWO shouted: "I've got two locks, three o'clock, low . . . three solid ringers." We were in trouble.

"Ten seconds . . . doors" the RN stated. I could feel the humph as the bomb doors opened. Time seemed to halt.

"Release," and I felt the aircraft quiver, becoming 60,000 pounds lighter.

"Break right, break right." EWO called out. I knew the maneuver well.

I cranked hard right and forward on the yoke and almost laid the old girl on her side, hoping she would fall out of the sky quicker than the SAMs could readjust for our position. Less than ten seconds later, at over 500 KIAS and ten thousand feet closer to the ground I saw the brilliant yellow-orange flashes of the two SAMs pass directly in front of my windscreen. Two hundred feet after they passed, the detonation was enough to make my eyes blur, but we had not been hit - - fortunately we had made it below them. The trick now was to regain some control of the ever plummeting aircraft.

I saw Capt. Learner cut the throttles and assist with pullback on the yoke while I deployed the spoilers. Another five agonizing seconds passed until the aircraft thankfully began to stabilize. Only then did I add power, while nosing the aircraft up slightly. I heard Learner shouting: "Navigator, get us the hell out of here."

Lt. John Cornelius our new Navigator gave me the PTT heading, (Post Target Turn) and I banked the Buff sharply to the right and put us on course which would take us back to the Gulf and out of harms way. I had just convinced myself that all would be well and I could relax in a minute or two when the EWO again came on the headset and announced that we had three more SAMs tracking us and they were closing quickly. I heard my copilot let out a harsh obscenity and I couldn't have agreed more. To make matters worse, we had now entered the area where intense AAA was concentrated and at our present altitude, we were trophy-case material. I began to feel the explosions from the 37mm AAA all around us . . . the sound of shrapnel bouncing off, and imbedding into the aircraft was the equivalent to a severe hail storm in the Midwest during spring.

The RN began to say something but his voice was lost in a major explosion. The concussion which followed I can only imagine have been worse if we had actually crashed the aircraft into a mountain. We had been hit by a SAM just forward of the bomb bay and it was obvious from the first moment of the incident that that this wound could be terminal.

The cockpit filled with a foggy mist and I could see electrical sparks scattering all around me. Caution and system lights began to flash and the scene was reminiscent of penny arcade gone mad. By the time I realized what had transpired and gotten my wits back, the aircraft was trying to execute a shimmy movement which I am at a loss to explain . . .sort of like a snake slithering across the desert . . . which told me our rudder control was marginal at best. Trimming the craft out as quickly as I could I called for Damage Assessment. It was then I felt the second explosive impact. This time we had taken AAA damage to the number 3 engine pod -- again lights began flashing; this time fire control warnings. My number 2's hands were dancing on the panel to pull the fire bottles and shut down the engines.

It was really a strange feeling as the number 3 pod tore away from the aircraft. For all the alarms, racket and confusion, I could physically feel the pod separate. Ironically, the missing pod did not induce any more ill handling characteristics in the aircraft than I had been experiencing before. . . or we were so past that limit that it didn't matter. By this time in the event, we should have been hopelessly out of control and on our way to Charlie's terra firma.

"Archer 02 -- you're on fire," came the call from another Buff crew. I am not sure who made the call, but it almost had to be Archer 03 who had been above and behind us.

Learner leaned over in his seat and confirmed we were on fire and that the aircraft was losing fuel at a high rate from number 4 tank. Shutting down the fuel and the cross feed seemed to do nothing to inhibit the blaze, which by now, the aircraft behind us was reporting, ‘was running past the entire length of the fuselage.'

"Damage assessment -- RN and EWO are bad, sir." There was panic in the navigator's voice. "Probably dead. Gunner's dazed but superficial -- I'm OK, I think." Lt. Jim Grant was partly correct, later he would lose a leg to his wounds. "We've got some serious air-conditioning back here." Decompression explained the foggy cockpit.

The question of if we were going to lose the aircraft was only surpassed now by when we would lose it. Fatally damaged as she was, the girl made a valid attempt to stay airborne. Despite the fire or the pod loss, with proper trim and constant coaxing on the yoke, we remained relatively stable. I kept thinking to myself that I should give the bailout command before the aircraft disintegrated in a ball of flame but at the same time I knew none of my crew had any desire to become POW in Hanoi. Some time ago we had discussed it and capture was not a viable option.

"I think we might make Red Crown if we're lucky," my number 2 mumbled. He had been doing some quick checking of the instruments and mentally figuring the distance from where he thought our position was to the US radar cruiser stationed in the Gulf. Shortly after relaying that information to me, number 1 pod mysteriously flamed out. The instruments still read full power and fuel feed showed pressure however you could feel the engines stutter and die. To this day I have no idea why or what perhaps caused it. On the plus side, almost the exact instant we lost power in number 1 pod, the roaring fire on the starboard wing extinguished itself and we quit burning. Fair exchange was no robbery and I willingly traded the fire for loss of power in pod 1.

I scanned the instrument panel and ironically some of the gauges were still functioning. After a quick glance I could see that we were at 16,000 feet, in a shallow dive losing about 1100 feet of altitude per minute. Our speed was down to 165 KIAS and I suddenly remembered in all the confusion I had neglected to retract the spoilers.

"Red Crown . . . distance?" I barked.

"Sixteen minutes . . . I think . . ." Learner hesitated, "I don't think we can make it ."

"We'll get close . . . we're not punchin' out here," I snapped back. Ahead in the distance I could see the coast and the beginning of the Gulf. In another minute we would be feet wet, over water.

"Make the call?" Learner asked, referring to declaring MAYDAY.

"Not yet . . . not till we're feet wet." I didn't see any future in allowing Charlie to know how hurt we were and let him send a MIG up to finish us off.

"Archer 02 . . . . Cowboy 3 . . . I have a visual and will stick with you as long as I can." It was one of the F-105 HK teams who had spotted our dirty vapor trail and would ride shotgun for our wounded bird. He then gave us a true heading for Red Crown and I again turned the aircraft.

"Roger that, Cowboy 3 . . . appreciate the assistance," John Learner replied.

My mind was racing with ten thousand thoughts . . . mass confusion prevailed. "Nav . . . recheck the boys . . . make sure."

"Negative, sir . . . they're gone." Capt John Cornelius replied.

Two of my aircrew were dead, my aircraft was in its final stages of death throes and I should have been petrified . . . instead I became very angry.

"Cowboy 3, . . . if you got a fix on those sites, go get um'," I radioed. "Forget us, we're junk anyway."

"Roger that Archer 02, I gota' fix . . . good luck, buddy." I could tell from the Thud pilot's voice he didn't hold much hope for our making it to Red Crown.

I think about that time I became totally involved in just flying the aircraft -- attempting to hold altitude and stay in the air. I know there was a long period of silence where John and I said nothing -- both of us knowing the job which had to be done and conversation was unnecessary. Perhaps the sounds of a dying aircraft, the wind and the screech of the four remaining engines was all that was necessary. When the time came, I felt his nomex-gloved hand tap my shoulder.

"Altitude," he said, pointing to the altimeter. We were at 4000 feet and still in our shallow dive. "We need to make the call now." He was right.

"Nav, make the call . . ." I could hear the MAYDAY distress call being repeated along with our assumed coordinates. After receiving Red Crowns reply, I reluctantly gave the abandon aircraft, order.

I watched as the red abandon lights came on - one from the gunners position and one from the RN seat. Nav must have used Jackson's chair. Looking across at my copilot I motioned to the hatch above his head. Nodding in reply he gave me a thumbs up, mumbled something I couldn't understand, rotated the handles on his seat, arming the seat and blowing the hatch. I saw him grin as he squeezed the triggers and the next instant he was gone in a flash, just like in the training films.

As command pilot of Archer 02, I had run my mission to the best of my ability, stayed with the ship until my remaining crew had ejected safely and now was alone in the aircraft. Now heroics left . . . it was time to go. I stowed my yoke, tightened my belts and armed my seat. A moment later I assumed the ejection position and squeezed the triggers. Strange, but at that very moment I think I began to say something . . . corny, like ‘see ya baby' . . . a pilots classic goodbye to his aircraft . . . but he explosion under my seat and the excruciating pain in my back somehow blocked out the words.

I don't remember much between then and the time I was being hauled out of the water by the crew of the HH-53 jolly green rescue chopper. I was wet, in terrible pain and depressed, feeling I had lost my aircraft and failed my mission. The only concession was that four of us had survived the blast and ejection, perhaps to live and fly again. Regardless, the bodies of my EWO and Radar Navigator were never recovered and closure of that would take years to put behind me.

I saw Learner one last time while in hospital in Saigon. He was returning to Andersen and was going to be given his own command. He was a good man and would make an excellent command pilot. His parting words, although very complimentary, did little to comfort me with the pain of loosing my aircraft and two members of my crew.

"You're a class act, Drackie' . . ." He quipped, beaming with his usual ice water smile. "It's been a real trip." Some years later I learned that John was killed in a pleasure boating accident down in Georgia, which was his home. I somehow know that when he left this world it was with a foul word on his breath and that patented smile on his face.

As for myself, I was still angry, and would stay that way for quite a few years. Angry enough that I was moldable . . . putty in the right sculptors hands. Angry enough to volunteer for other missions from another agency of our government who convinced me I should fly F-111's into Laos and Cambodia. Getting even can become an obsession . . . but that's another story all in itself.

I Watched a Student Pilot Solo Today...

I Watched a Student Pilot Solo Today...

By Sean"Crash" Reilly, WWAL's EVP

Marketing & Co-founder

(July 26, 1998)

Today I witnessed what may have been a student pilot’s first solo and – hours later – I am still smiling ear to ear.

Working near a small regional airport (Schaumburg Regional, Schaumburg, IL), I often find myself lunching there in my car, watching the comings and goings of small aircraft, monitoring UNICOM on a hand-held radio, and dreaming of the day when I might be one of those lucky pilots on final. Today was more exciting than usual however… today I observed a student pilot in what might very well have been his first solo flight in the pattern.

It all began with what appeared to be a typical lesson (instructor in the right seat). It was quickly apparent by the way the student taxied and handled the plane, however, that he must have already logged several hours. He started with standard pattern work (touch and gos) with one simulated "engine out" landing (which the instructor announced on UNICOM). That one captured my full attention as the pattern he flew was markedly shorter than the others – steep and tight with nearly a mid-field touchdown. Made my adrenaline race… and I was sitting safely on the ground! One circuit later, I heard the plane taxi to the FBO and, after a few moments, it taxied by me with only one pilot aboard. "It’s show time!" I thought. Sitting up straighter now, and discarding the remnants of my KFC lunch, I focused intently on his aircraft, wondering what was going through the mind of this airman as he glanced to his right at what had to be an eerily vacant seat beside him? I swallowed hard just thinking about it. "Oh yes… definitely show time," I thought.

As the student taxied toward the active, he asked his instructor (who was now on the tarmac with a hand-held radio) if he could skip the runup. "No need to," responded the instructor in a slightly annoyed voice, "If it’s running fine, just keep on going." Almost timidly, the student announced he was taking the active (runway 29) and he began his take off roll. Liftoff was uneventful but his UNICOM calls immediately following departure weren't sharp. A lack of confidence was evident in his voice as, when he turned crosswind, he mistakenly announced he was "turning base" and later, as he announced he was "33 Warrior" when the N number on his Warrior read 66 Whiskey. Jitters. Would I be any less nervous? Heck, I was nervous just sitting in my car watching the situation unfold. Had to check my palms for sweat.

Well, the student's first landing wasn't one for the record books. In fact, it turned out to be a non-landing. As he announced he was turning final, I could see he wasn't steady. He was up, then down, then left then right – then he floated in ground effect and wobbled about a quarter of the way down and slightly above the runway before conceding that this wasn't going to be his first solo landing. His instructor, now standing on the infield reassured him via his hand-held, as the Warrior lumbered its way skyward again, that he made the right choice. "Watch your speed!" he barked. "66 Whiskey, going around. Staying in the pattern," dejectedly announced the student, probably pondering his aborted moment of glory (assuming he had time to ponder ) and recalling all the good landings he made with his instructor in the seat beside him.

As the student announced he was turning downwind, his voice changed slightly. Was that determination I was detecting? His calls were crisper with a hint of frustration mixed in, perhaps. "This is it," I thought as he executed a clean base turn. "He is not going to be denied." A second or two later, I heard a determined announcement of , "Schaumburg traffic, Warrior 66 Whiskey turning final for 29 Schaumburg." No wobbles in his voice or on the approach this time. 66 Whisky came down straight and true, accented nicely by the squeak of his trusty steed’s wheels on the runway. He did it!! I swear, if others weren't nearby, I would have stood up and cheered for him. I was all smiles. So too, must he have been (and perhaps a bit relieved). But it wasn't time to celebrate just yet…

The plane didn't slow. Instead, the engine growled to life as 66 Whiskey began its charge down the runway like a bull after a matador. Encore! He wasn't through yet. He wanted – and perhaps needed – to go around and prove to himself that he could land 66 Whiskey again. Turns out he executed three more touch and gos. With each circuit, the confidence in his voice grew. This student, who began his day humble and flustered, now sounded like the captain of a 747 – HUGE confidence which grew with each subsequent and improved landing. If a smile is audible, I was most definitely enjoying a symphony of smiles in his UNICOM transmissions!

As I pulled out of Schaumburg Regional’s parking lot and headed back to the grind, it dawned on me that I don't recall having ever been happier or more excited for a person I didn't even know. This was perhaps one of the most exciting days in this student pilot’s life and I was there, sitting in my car beside runway two-niner, Schaumburg, eating lunch and monitoring UNICOM, to anonymously share in his big event. Heck, I felt like the proud father of a newborn child. I can only guess how this student pilot and his instructor felt.

There is nothing in the world like flying. Today’s lunch was a special one indeed.

Classic Flying: Great Times Remembered

Classic Flying: Great Times Remembered

By WestWind's Darden Newman

(July 25, 1998)

Well, you've done it! You have stirred the juices of my old flying blood to the point where I just have to ruminate to a degree.

In my limited experience I would say that the purist form of flying resides in two aircraft, the J-3 Cub and the Stearman PT-17. If you EVER have the opportunity to ride in these two craft I think you will agree with me. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to get in a number of hours in both.

Picture this. Flying in a J-3 Cub at night, calm air, with the lights of the city twinkling below you and having just the barest of instruments with a Motorola Airboy as your only means of communication. The "Airboy" was powered by two "D" cell batteries.

We were allowed to fly at night (solo) only if we would stay within five miles of the airport and keep the rotating beacon in sight. This requirement was made so that if for some reason the batteries went out the tower could shoot us with the red light as a signal to return to the field. Communication with the Airboy was one way; we could receive only. When we returned to the field we depended upon the light signals for clearance to land. Red light on the base leg as a signal not to land (incoming traffic) or a green light, clearance to land.

The Stearman was pure joy! I had 25 hours of acrobatics in it. There I was in my helmet, goggles, and even a white scarf! Baron von Richtoffen had nothing on me! You could put that airplane in the most God-awful attitude possible, just cut the throttle, let go of the stick and it would fall out in level flight.

On approach you could cut the throttle on base and let the wind sing through those struts and when you banked so that the inboard wires were level with the horizon you were executing a perfect bank. If you were a little short just give it a shot of the throttle and let it settle on down and as you crossed the fence you gave it just a touch of throttle and planted both wheels on the asphalt, pushed the stick slightly forward to hold the wheels on, cut the throttle and gradually let the stick come back as the tail settled down. Once done you had executed a perfect wheel landing. Damn, Sean, that was the greatest feeling in the world!

Well, I am now confined to the "virtual" world but at least I have some fond memories. BTW, there was a short feature on our local TV last night about a Globe Swift aircraft museum located at Athens, Tennessee which is about 55 miles northeast of Chattanooga. The Globe Swift is a two seater, all aluminum, low wing plane first made in the 40's; a few were built after the war in the early 50's. If you have never seen it, it is one of the most beautiful little planes ever made. As I recall, it would tool along about 130 - 135 knots and was considered an airplane "ahead of its time" back then.

I was thinking I might take my 35 mm camera and go up there and do a feature about the Swift and maybe the WWAL guys would be interested in that. What do you think?

Vietnam Remembered

By Bill Blankenship, WWAL's VP of Flight Ops (May 18, 1998)

It was December 1969 and I was stationed in Tuy Hoa, Vietnam with the 39th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron. I had been in the U.S. Air Force just a year and a half, receiving my orders for Vietnam at Pope AFB, North Carolina, in September 1969.

Due to the political climate, our sensitive mission and the fact that we found ourselves flying frequently over Cambodia and Laos, we had to fly all our missions, not out of Vietnam, but rather from Udorn, Thailand. The reason for this was, that if we were shot down and/or captured, the government could say we were on a peaceful flight from Thailand that had nothing to do with the war in Vietnam. Our "true" mission was to locate downed US pilots, orbit (fly circles) above them and radio for a helicopter (Jolly Green Giant) to pick them up. During the trip back, we usually had to refuel the helicopter in flight, due to its limited range. By the way, we flew HC-130P Aircraft. Our planes were equipped with refueling pods on both wings, external fuel tanks on each wing, a 18,000 gallon internal fuel tank for refueling the "choppers", two "scanners" windows, one on each side of the fuselage forward of the wings, and "JATO" (jet assisted take-off) capability. It was even equipped with scissor hooks on the nose for picking up a person stationary on the ground, although we never did that. We would take off from Tuy Hoa, Vietnam and fly to Udorn, Thailand and receive our assignment there. The flight took about two and half-hours each way.

On this particular day, we received our briefing at Udorn and took off to locate a downed Marine fighter pilot. A Coast Guard Captain on TDY (temporary duty assignment) was pilot-in-command, while I flew as co-pilot. We found the missing pilot just inside Laos, established our "orbit" and called for the "Jolly Green". Upon a successful rescue, we headed back to Udorn. While we were actively refueling the helicopter, our Flight Engineer questioned "what’s the Navy doing way up here?" He asked because he saw a silver jet, knowing that only the US Navy flew non-camouflaged fighters. We all quickly discovered that it was a North Vietnamese MIG fighter as it zipped below us and turned for a wide 180-degree turn. Our Captain immediately ordered an emergency "disconnect" from the Jolly Green, whereby he pushed the C-130 in a steep nose down dive with the refueling line still outside the pod. The Jolly Green veered to the left and also tried to lose altitude fast. It was too late for the chopper though. The MIG had already shot a missile and the helicopter was nothing more than a ball of flames. In the meantime, we dove very near to tree top level before leveling off. During our emergency descent, we exceeded the 180-knot speed limit with the refueling line extended and tore the line completely out of its pod, causing fuel to stream out of the wing. We all scrambled to locate and find the MIG from every available window in that C-130. We never saw him again.

We radioed Udorn for an emergency landing and the ambulances and fire trucks were lined up next to the runway as we landed with fuel and hydraulic fluid flowing from the left wing. Upon coming to a complete stop, the "scanner" sitting in the left scanner’s window had to be physically removed from the aircraft and taken to the hospital. He couldn’t talk and just shook and stuttered uncontrollably. He had "buddies" in the Jolly Green and saw them all disappear into a ball of fire when the missile struck the chopper. We all checked the entire plane for bullet holes but could find none. Upon tying off the fuel lines (or so we thought) to the refueling pods, we were ordered back to our home base at Tuy Hoa for repairs. In addition, we were also ordered to fly about 30 Army Soldiers back as well. During the trip back, it became apparent that we had a hydraulic leak. Our crew chief had to pour cans of hydraulic fluid into the reservoir every 15 to 20 minutes, in full view of the troops we were carrying. Believe me, that was the quietest bunch of soldiers I ever saw. We also had to forbid any smoking because we were unsure of the fuel lines and suspected an ongoing leak in some of the transfer lines. By the time we landed at Tuy Hoa, we were very low on hydraulic fluid and fuel but made it in one piece. The next day, the news from the maintenance people was very frightening and all we could do was just look at each other, speechless. It turned out that one fuel line was not capped correctly and the least little spark could have turned our plane, and everyone in it, into a fireball. <gulp>

Well, that was my first real experience of the war. There were a few more to come. Like the time we had to make a downwind landing at Da Nang because there was a fire fight occurring on the downwind side of the Airbase. We had soldiers and their gear "disembark" our plane without us ever coming to a full stop. But that’s another story.

While several of my buddies did not return from Vietnam, I landed at Mc Chord AFB, Washington on 9/29/70, in the middle of the night with no one noticing. During the lonely taxi ride to the hotel, I felt as though I had just stepped out of a time machine. The mental adjustment back to "peace" took a while.

I’d like to leave you with a poem. A soldier I knew wrote it. He never made it back.

In

Vietnam This is the life I have to live, You have a ball without near trying Use your drugs and have your fun It’s a large price he had to pay He bought your life by giving his

|

Management note: Never forget, or fail to thank, all our veterans for the enormous sacrifices they made for our country. Thanks Bill for sharing this story and poem with us.

CASA 1-131 Jungmann

By WWAL's Gene Popma

Several years ago, my lovely wife Ann and I purchased a Bucker Jungmann. The original Jungmann started life as a simple economical low-powered primary trainer for Goering"s clandestine Luftwaffe schooling organization, the Duetscher Luftsportverband (Dlv). Its designers were Carl Bucker, ex-navy pilot in WW I, and Anders J. Andersson. They designed and built the Bucker from scratch in under six months, and began manufacture in 1934.

Intended for "strength with lightness", the aircraft was a masterpiece of Teutonic thoroughness and efficiency. Although it weighed under a thousand pounds, it was stressed to an immensely strong +/- 12 g’s. The aircraft handled so well that it was immediately ordered into mass production as Germany’s main basic trainer. It was later exported to many European countries, South America, South Africa, and even to Japan.

Three or four thousand were built in Germany; most of these were broken up after WW 1. Those most commonly seen in our skies are the ex-Spanish Air Force ones, manufactured under license by Construcciones Aeuronauticas SA (CASA). CASA built 530 before production petered out in 1963.

Our Jungmann was manufactured in Spain in 1959, and used by the Spanish Air Force until 1975 at which time it was disassembled, crated and shipped to the USA in pieces. The aircraft was certified in 1983 as Experimental and I flew it over 100 hours in the original configuration. Later we installed a Lycoming O-320 150 HP engine and Ellison carb, and rebuilt the wings and cabane.

Knowledgeable pilots call the legendary Bucker Jungmann the best handling sports plane of them all. I have flown the Jungmann over 300 hours in aerobatic flight. It performs just as its reputation says. The inverted fuel and oil system allow inverted flight and maneuvers with no hesitation. The plane is stable in any position including knife edge. It doesn’t stall, just floats. I can do a seven turn spin with only 700' loss of altitude. Although it snap-rolls in 1.5 seconds, one can take as long as 23 seconds to complete a slow roll.

The Aviators world is full of joy and satisfaction. There are so many kinds of airplanes that fulfill our desires to be aloft. The Bucker Jungmann is a marvelous way to fully experience all three dimensions.

Management note: Gene is a ex-naval aviator who flew dive bombers off the USS Lexington in the South Pacific during WWII. His other ratings include COM, SEMEL, SES, INSTRUMENT, GLIDERS, AEROBATIC-AIRSHOWS, LOW LEVEL WAIVER, AND CFII. He has logged over 5,000 hours from taildraggers to jets. Gene lives on a private residential airport in Illinois and is a retired AT&T executive.

Never Again: A Sign of Ice

Never Again: A Sign of Ice

By Robert P. Mark

This article appeared in the November '96 issue of AOPA Pilot Magazine. Used with permission of the author. ŠAOPA Pilot Magazine.

Inexperience, stupidity, get-home-its — take your pick. Any of them applied to me one late November evening as I cruised over Chicago's Loop with an electric night sign slung beneath the belly of an old, but well running Champion Citabria.

It was supposed to be a routine sign trip over Soldier Field adjacent to Merrill C. Meigs Airport. I'd flown the trip many times before and I knew the area well. I had about 400 hours and a commercial certificate under my belt, but I was still working on my instrument rating.

The night sign was usually hung on the Champ in the fall when the nights were longer. It was an old design that resembled a chicken-wire cage running from wing tip to wing tip underneath the airplane. To the aircraft owner the sign meant extra income. To a pilot the sign meant extra drag.

As I prepared for the flight from Palwaukee Municipal Airport, I was aware that light snow was forecast, but not for nearly three hours after the job would end. Unfortunately, as I approached the plane, I noticed it leaning to one side because the right main tire was flat. After some quick phone calls to the customer about the delay, I managed to find the night mechanic to fix the tire. More than an hour late, I rushed to get airborne into the now darkened sky.

I hadn't checked the weather for almost two hours, but when I did, DuPage Airport to the west was still good VFR. I didn't think to check the weather at Rockford, about 30 miles northwest of DuPage. If I had, I would have known that it was 200 overcast and a half mile in snow.

I turned on the night sign while still about six miles north of the target, figuring that the customer had the extra bit of time coming. I circled around the target numerous times, and the conversation with the tower controller at Meigs made it tough to tell who was more bored. I'd been over the target for perhaps half an hour when I saw lightning to the west of the city. I called Chicago Flight Service and learned that DuPage was IFR in snow, with a thunderstorm, too. I had to do something. But with only $3 in my pocket, I wouldn't even be able to pay for the cab ride back to my apartment if I landed at Meigs. I made a few more passes around the target to give the customer his money's worth before I bade the Meigs controller good night and headed north up the Lake Michigan shoreline toward Palwaukee. Actually, Palwaukee is northwest of Meigs, but I didn't like to fly over the city at night in a single.

Three miles north of Meigs, drizzle began that sounded like thousands of tiny grains of sand hitting the plexiglass windshield. The visibility was still good, so I figured that I was home free, even though the outside air temperature was near freezing. As I looked toward my destination, I realized that some of the city was beginning to disappear in the precipitation. I thought about it for a minute and decided that it was time to break my rule and fly over the city.

The intensity of the rain seemed to increase, but only for a short time. Then, the only sound was the constant drone of that 150-horsepower Lycoming. It took me a few minutes to realize why it was so quiet and why I no longer saw the rain streaming across the windshield. It was freezing. I saw tiny drops of ice clinging to the struts and tires; but, most of all, it was clinging to the hundreds of little pieces of wire on that big night sign.

As I looked behind me to the shoreline, I decided that I couldn't turn around. Palwaukee, now six miles ahead, was reporting three miles visibility in freezing rain. I did the only thing that I thought I could—I climbed—hoping to give myself more time once this big block of ice decided to come down. Straight ahead, the rotating beacon of what was then the Glenview Naval Air Station seemed to beckon. For years, I'd been told that civilian airplanes were not allowed there except in emergencies. The lights of Glenview's 7,000-foot runway reflected off the ice on my sign as I passed over the field.

Palwaukee was two-and-a-half miles away as I flew a straight-in approach to Runway 30 Right on a Special VFR clearance. Even though I was still holding full power, the aircraft began to descend from 1,500 feet agl. A mile out on final, I was down to 400 feet agl. The icicles hanging from the night sign looked like stiff tinsel. I held full power almost to the ground. About six feet above the runway I began easing back on the throttle. As the rpm slowed through 2,250, the old Champ gave up the fight and fell to the runway. I don't think that airplane rolled more than 200 feet before it stopped. The snow, sleet, and freezing rain were now so heavy that I could barely see the tower a half a mile away.

As I taxied closer to the fuel pumps, I watched the line attendant's eyes widen. I shut down and took a few deep breaths before I got out. Now it was my turn to look surprised. The little taildragger looked as though it were encased in clear, shiny plastic.

After I tied the airplane down, I headed for the airport restaurant and some coffee. I ran into one of the charter pilots I knew and told him what had happened. "Why didn't you land at Meigs?" he asked. "Why didn't you declare an emergency and land at Glenview?" he continued. "Why didn't you keep closer track of the weather? What kind of decisions are those?" By now, I realized that most of my decisions had been pretty bad.

I had been presented with plenty of options but had been too single-minded to see them. In general, I took too long to make my decisions. I learned that there are always other options, but you have to look out the windows and see them.

Rob is a 5,100-hour ATP and CFII-MEI who has been flying for 29 years. He also just applied to fly for WestWind Airlines and is Sean "Crash" Reilly's brother-in-law. Poor guy! Never Again" is a regular column in AOPA Pilot Magazine presented to enhance safety by providing a forum for pilots to learn from the experiences of others.

Frozen Runways - Large and Small.

Frozen Runways - Large and Small.

By WWAL's Jesse R. Callahan (January 20, 1997)

Shortly after I retired from the USAF in 1963 I found myself sitting in the middle of the Greenland ice-cap at one of the DEW-line sites. For those too young to remember, the DEW-line or Distant Early Warning line was a chain of surveillance radar sites operated by the Air Force in the extreme northern latitudes to keep an ear and eye on the Russians. The line extended from the far reaches of Alaska, across Canada, Greenland and over to Iceland. Our sites were know as dye sites and we were supported out of Sondestrom Air Base on the West Coast of Greenland. Dye 2 was situated about half-way across the ice-cap at the 10,000 foot level. We were supported three days a week by ski equipped C-130s operating out of Sondestrom.

A 6000 foot runway was laid out on the ice with lights along the sides and threshold markers at the ends. On the approach to the runway beginning about 2 miles out, black flags were placed in line with the center of the runway about every 500 feet. At night in the clear, cold atmosphere of the cap, the lights were visible for several hundred miles out. SAS flew a polar route across the site, and also maintained a hotel in Sondestrom for their crews. Occasionally there would be a new crew flying across at night and, of course, they were intrigued by the runway lights out in the middle of nowhere. Often they would ask, "How long is your runway"? Our stock reply was that it was 6000 feet long, 300 feet wide and it had 400 miles of over-run on each end!

On the East coast of Greenland was the little Eskimo village of Kulusuk. At that location was Dye 4. During a very bad storm, with winds in excess of 180 miles per hour, the entire site was blown away -- into the Danish Straits. All the equipment required to replace the site was to be flown in from Dover, Delaware on 13 C-124 Globemasters. This would have been okay except the little runway at Kulusuk was only 1700 feet long and the apron would only accommodate two, at the most, C-54 aircraft which TWA used to supply the site. Thirteen C-124s were dispatched en mass from Dover and flew to Kulusuk. When the lead aircraft commander arrived over the site and saw the facilities on the ground he flat blew a gasket. All the birds had to turn around and fly back to Goose Bay Labrador and then be dispatched one at a time since there was only room for one airplane on the ground.

This was one of those rare logistic snafus for the Air Force.

Management comment... Hey, look at the bright side, they all got plenty of stick time! Sure beats pushin' a pencil all day.

Thrill of a Lifetime

Thrill of a Lifetime

by Mike Obermeyer (January 11, 1997)

As an illustrator in the Air Force Art Program, I get the chance to travel and get some great behind the scenes tours for reference for my paintings. I'm also given the rank of Colonel for these tours. I've had the opportunity to tour Edward's AFB with the Secretary of the Air Force as he delivered the first operational B-1 Bomber. I've been to many rocket launches, toured the B-2 assembly line and had the chance to go to the South Pacific and to Bosnia as an Air Force historian. I'm also a private pilot so I have a huge interest in the subject. Nothing compares, however, to the thrill I got to experience this past June.

The Air Force offered me a tour to Panama and Columbia to tour the Counter Drug Air Defense Ops down there.We'd be flying down on a KC-135, refueling a squadron of F-16s from Fargo, North Dakota. We'd then fly down to a remote radar site in the Amazon on a C-130 (riding in the cockpit during take-off and landing). Then the unexpected -- I was chosen from the four artists on the trip to possibly get an orientation ride on an F-16 while in North Dakota. Approval was finally granted (and stick time for me included) and, after a week or so of sweaty palms, the day finally arrived.

I arrived at the Air National Guard Base at 8 a.m. for a noon flight. I went to Life Support to get fitted for a G-suit, helmet, oxygen mask, boots, flight suit and was trained on the use of oxygen. I then went for some ejection seat training for about an hour. There was so much to learn: how the seven point restraint system works, positioning for ejection, how to use the emergency parachute, etc. I just hoped I'd have the presence of mind to remember any of this if anything actually happened. After this load of information, I got to fly the simulator to familiarize myself with the controls of the F-16 and to shoot some bad guys out of the sky. Finally, we had a pre-flight briefing to talk about our flight. It was actually going to be an hour and half training mission to practice making I.D.s on another aircraft (in this case, a USAF Learjet). This would simulate a real mission out of Panama -- making an I.D. on a drug-ferrying aircraft.

We went out to the F-16 on the flight line, took a ton of video and pictures, of course, and strapped in. I soon realized that I'd just about forgotten everything I'd learned in Life Support. Who cares -- I couldn't believe I was sitting in the rear seat of this awesome aircraft. I felt the ultimate in COOL as we taxied out to the runway (the base is located on a municipal airport, so we got lots of stares). I knew I'd be tested right away -- our departure would be a full afterburner, vertical takeoff to 15,000 feet. After several nervous moments, we were cleared for takeoff and my pilot, Major Rich Gibney, lit up the afterburner and we moved down the runway. I looked for something to hold onto and at 300 knots, we went up. I could hear myself groaning to try to counter the G-Pull on my body. It was incredible. I felt like a shuttle pilot. The horizon was straight back behind me as we climbed to altitude. It seemed like it only took about 10 seconds. Very smooth. Once level, he did a few rolls and had me try some right away. What a feeling, very easy to roll. The stick is on the right console. Just pull the nose up 10 degrees and move your wrist to the left and the world turns. The visibility in the F-16 is almost too good. The curved canopy enabled me to look almost straight down and the lower edge came down to about my knees. I felt like I was sitting on top of the plane. I had a radar screen in front of me which I could switch to a HUD (at one point, I attempted to do exactly that during a high-G turn and could barely extend my arm). We did a few more maneuvers -- a barrel roll (very smooth, no sense of motion), a split-S, some slow flight at 150 knots and, of course, we went up to Mach 1. That was uneventful -- smooth and quiet. I got to fly it longer than I thought I would. He had me circle a small town as we waited for the Learjet to arrive and I took it down to 3,000 feet to fly through a layer of broken clouds. Watching our shadow move across the farmland below really gave me a feel for how fast we were flying -- a huge difference from the Piper Cherokee I fly.

We mad three I.D.s on the Learjet, first finding it on radar and the visually closing in from behind to within ten feet of the tail to read off the serial number. On the final attempt, the Lear used his radar-jamming equipment, so things got a bit tougher. We finally found him visually and kind of got into a chase with the horizon swinging every which way as he tried to elude us. We were eventually able to lock him into our sights and "shoot" him out of the sky.

On our return to the airport, we did a few low-level (about forty feet), high speed fly-bys with some high G climbing, 90 degree bank turns back to the pattern. That was the wildest part of the ride. As I was forced down into my seat by the turn, I looked back to see the vapor coming off the wings and the passenger terminal of the airport above me at about 2 o'clock.

After landing, I was given a video of the flight -- a black & white view from the nose of the HUD and all our communications included. Unfortunately, I had to give back the helmet and oxygen mask. Needless to say, this flight was the highlight of my career -- and one of the highlights of my life.

The guys at the North Dakota ANG (The Happy Hooligans) were all very helpful and seemed to share my enthusiasm for the flight. I really can't thank them enough. And I didn't get sick...

A note from Sean "Crash" Reilly. Mike is a friend of mine from California -- an unbelievably talented artist and not a bad Cessna/Piper pilot either ;-). When Mike got back from this trip, he called me and told me of his merry adventures. I saw his video pix. Way cool! Many of us (all of us?) can only dream of such an opportunity -- for Mike it was a dream come true! I'll envy him forever. BTW, the photo above is not his but I'm going to see if I can talk him into sending me a few to post here. Stay tuned.

"Things Just Ain't What They Seem!"

"Things Just Ain't What They Seem!"

By Jesse R. Callahan (January 3, 1997)

The year was 1946 and like a lot of other 23 year olds just back from WWII, I was anxious to resume 'civilian' flying as opposed to the hot military style we had become used to. I was still single and did not have too many responsibilities, so I plunked down a worldly sum of $400.00 and bought a surplus BT-13. I had taken my basic training in the Vultee Vibrator, as the BT was affectionately called so I figured it would suit my needs more so than the Mustang I had been eyeing. It cost $300.00 more, so that was out of my range.

At the time I was stationed at Kelly Field in San Antonio and was still dating my child bride up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. When we got a free week-end, I would usually crank up the old Pratt and Whitney 450hp engine and go tooling off in the blue to TUL. Back in those days we did not have such luxuries as VOR, FSS and Flight Following. We had the old Adcock Range (you know, A's and N's) and at night, the CAA light line. We relied mostly on following the iron beam, and when we would come to a town, we would circle the water tower to see where we were. Usually the town name would be painted on the tower.